I am reposting favorite helpful posts each Monday throughout March, April, and May.

My recommendations for a basic hair kit:

● Straight hair pins

● Faux tortoise hair pins

● Plain black elastics

● Hair Pomade

● A Plain net or two

● Faux horn hair comb or two

I am lucky enough to be able to purchase these items in person, includong the straight hairpins during a day trip through the Finger Lakes. Not everyone has similar local resources. With this in mind, I am including two shopping lists: one that can be done online from home and one that can be done mostly in person. The online list supports small businesses, with the exception of one item through Amazon.

Shopping from home for approx $38.00:

Order from Timely Tresses:

~~1 set of faux tortoise hair pins $4.00 or 4 chignon faux tortoise hair pins $5.00

~~1 plain hair net $4.00

~~1 back comb $4.00 or 2 side combs $4.00

Amazon:

~~2 sets of 12 straight hair pins in 2” or 3″ and 2.5” $12.00

Talbott and Co on Etsy:

~~1 tin of pomade $14.00

Shopping mostly in person for approx $25:

Local pharmacy:

~~Plain hairnet $2 for a set of 3

~~Faux tortoise hair pins $3

~~Hair elastics $2

Amish dry goods shop:

~~Straight hair pins 2 sets for $4

Talbott and Co on Etsy:

~~1 tin of pomade $14.00

Sources:

- Timely Tresses http://www.timelytresses.com/store/c20/Hair_Dressings.html

- Talbott and Co. https://etsy.me/3pH7zNH

- Beth Miller Hall https://etsy.me/3pJ1UXb

- LBCC https://etsy.me/3cGXdYB

- Amazon items: 2.5″ Straight hair pins

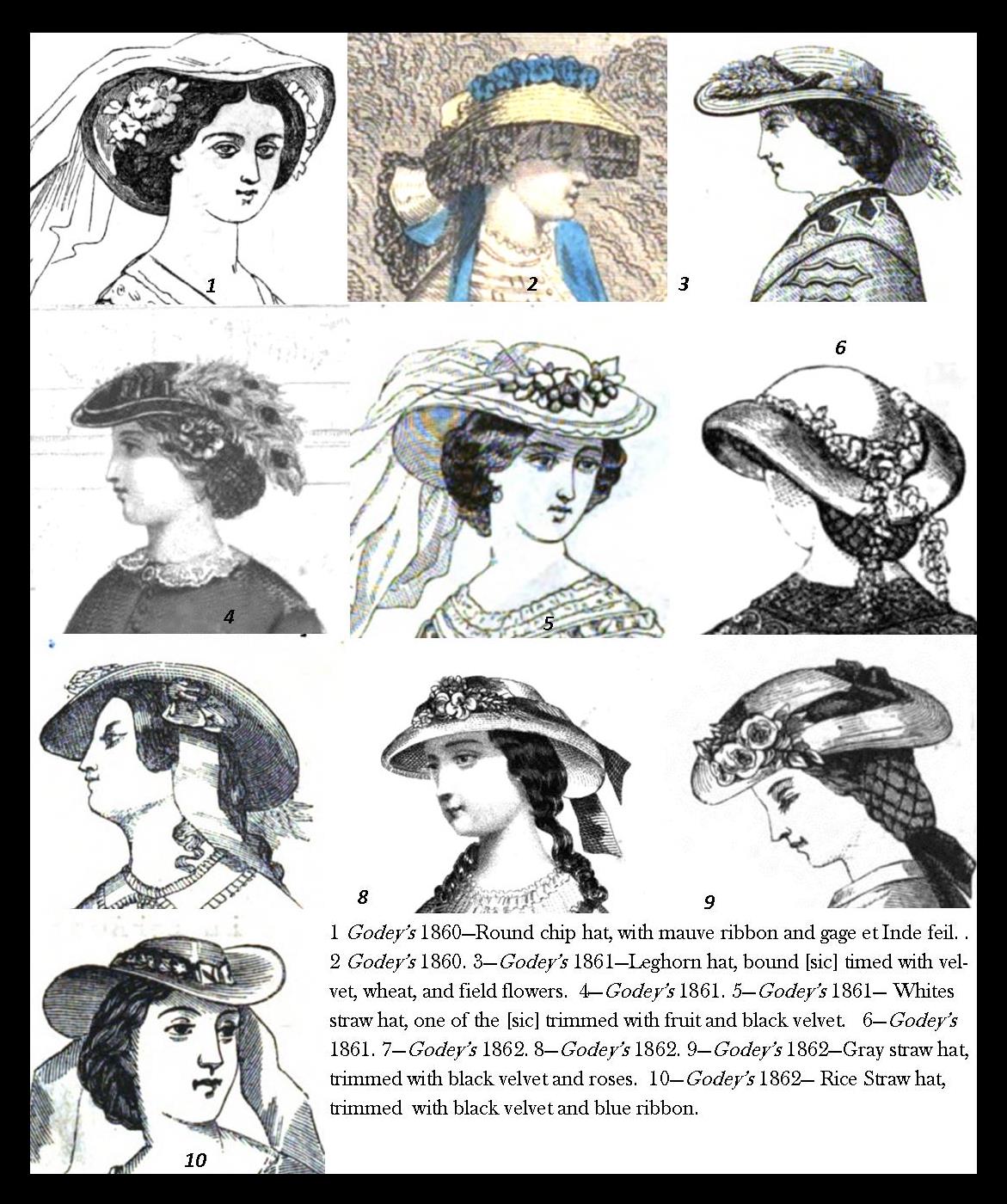

Are you one of the many readers enjoying my millinery blog posts?

Consider becoming a Patreon patron. Doing so helps support my work and helps me write more useful articles.

https://www.patreon.com/AMillinersWhimsy