What do my e-publications look like in print?

It took me far too long to find out…. they look fabulous!

I should have been having nice copies of each of my e-publications printed as I completed them as a way of fully feeling their completion and celebrating the work that went into them: the research, creation, writing, and formatting. But, life got in the way.

An invitation to do a book table at GCVM’s upcoming book theme weekend nudged me to finally get these printed. Thank You Lindsay!

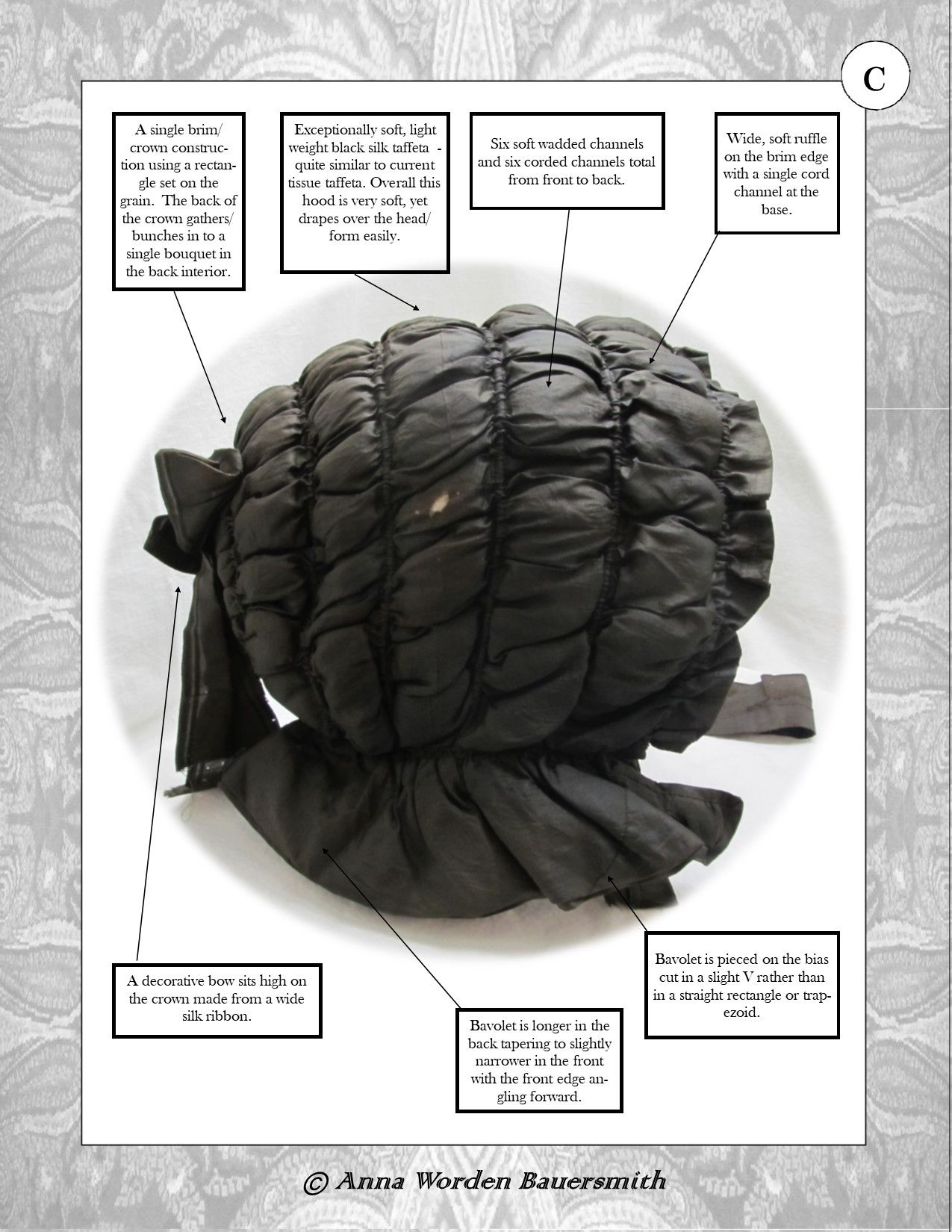

I stopped at my local Penny Lane Printing to see if they could make me copies of each of my main e-publications on a short turn-around. They came through with two copies of each: one for display at the event and hopefully future events, one for my bookshelf and records. (I keep envisioning copies of my book covers framed with their Library of Congress certificates.) I even threw in my In Detail series last minute.

Seeing them in print is gleefully satisfying. Penny Lane did a beautiful job with rich color. Flipping through, I am very pleased with both their work and my work. Seeing the layouts and images in print makes me happy, as well as grateful to my art and graphic design teachers. ✨️

I suspect there are two questions some of you are wondering….

First – Where is From Field to Fashion? I meant to cover this in the video but my migraine won out. Don’t worry, I will be bringing a copy of From Field to Fashion. FFtF was originally in print. I had another small print shop, that has since closed, print it. So, I have a couple copies. Another reason is I am also considering a new edition or much expanded book focusing on either the straw millinery industry or cottage industry as a mode of income for women in the nineteenth century. This would be another multi year project.

Second – Why don’t I offer printed copies regularly? I would love to be able to offer printed copies. Doing so was one of my first thoughts for this event. Then came the reality of pricing. With only doubling the cost of printing, prices would have been between $26 and $45 each. That said, I am exploring options. I may be able to redesign my shawl or hair net books to be black & white interiors, possibly with color plates. The other route, with less control, would be Amazon.